Putting Robots to the Test

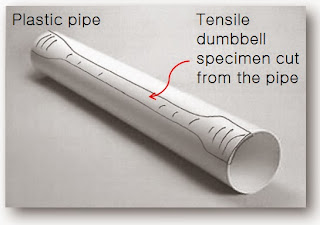

Successful manufacturing relies on quality and productivity. Testing machines are used to demonstrate the quality of raw materials such as steel alloys, composites, plastics and rubber as well as components including medical devices, packaging materials and fasteners. Manufacturing processes today are typically automated to a

greater or lesser extent, although the quality process is often manual.

This is generally time consuming, involving entering reference data, performing test procedures, reporting on the results, preparing the testing machine, starting the test, qualifying and accepting the results and appending comments before removing the

materials.

Historically, materials testing has been an operator using single or multiple stations. This can be uneconomical in terms of operator time where speed is crucial – for example in testing threaded fasteners for the aerospace industry, testing

is required 24 hours a day.

Drug delivery in the biomedical industry is one sector that could benefit from automation. Drug delivery tests are performed on three individual stations with multiples of those stations, lab operators working 24 hours a day loading, testing and removing the parts – this can now be automated.

However, there is a discrepancy in manufacturing where businesses are happy to pay for the automated manufacturing of products. The testing of the materials used in the products is still based in the domain of manual workers – no matter the size of the business or its industry. The high cost of introducing automated testing into the manufacturing process, and whether a business believes it has the volume of samples to justify them, has been a barrier to smaller companies considering spending the money to supplant human operators carrying out material tests with robots.

This has resulted in the development of scalable automated testing systems, which can offer manufacturing businesses an alternative to manual testing, with long-term benefits.

Figures by Tinius Olsen, UK, claim there are gains to be made, noting that an operator can spend 8.4 hours per 24-hour day watching and waiting for tests to run. A robotic system can run all day and night, leading to weekly gains of 59 hours against an operator, amounting to 127 days over the course of a year. This means more tests can be undertaken with increased productivity.

The technology can be designed, developed and scaled up or down to fit a business’ needs and be versatile to accommodate any material or components. The idea is it can run single or multiple tasks at any size or combination. Creating a scalable building block approach allows for systems from low force applications of just a few newtons to very high force applications of a thousand kilonewtons or more.

Olsen’s first machine, built in 1891, the Little Giant, was the first to combine and accurately perform tensile, transverse and compression tests in one instrument housed in a single frame. This same design approach is now seeing developments in fully automated testing, whereby multiple machines can be placed into a cell with a single robot control. This can feed multiple materials carrying out tests including hardness, tensile strength and flexibility.

Comments